The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of Bicycle Police

This is an excerpt from a paper written by Ross D. Petty, Babson College, in 2006. Download the full paper.

Introduction

The concept of police patrolling originated in England in 1818, after private rewards failed to deter crime and people were outraged when troops were called into Manchester to quell a civil disturbance and left 11 people dead. Sir Robert Peel introduced the Metropolitan Police Act of 1829, which set up metropolitan police districts, staffed by paid constables (Trojanowicz et. al., 1998). These “Bobbies” (nicknamed in honor of Sir Peel) were on duty 14-17 hours of the day and often patrolled 20 miles a day for weeks on foot without a day off. To verify their diligence, early constables had to leave a ticket at a designated home on the farthest point of their patrol.

Boston developed a similar paid night patrol in 1801 and in 1804 Detroit appointed its first team of civilian police officers. In 1844, New York City was the first American city to model its police department after the principals in Peel’s law that included offering service to all members of the public and maintaining a good relationship with the public (http://www.leineshideaway.com/PoliceHistory.html). Riots in many major U.S. cities from the 1830s through 1850s led to the formation of police departments in virtually every major U.S. city by the mid-1860s (Trojanowicz et. al., 1998).

The Rise of Bicycle Use

In the 1860s, the earliest pedal bicycles made of iron and wood called boneshakers appeared. The earliest use of the bicycle by police may have occurred in 1869 when an Illinois sheriff reportedly supplied himself and his deputies with these boneshakers (Dunham, 1956, p. 119). However, boneshakers, as the name suggests, were heavy, not very comfortable to ride on poor quality U.S. roads, and overpriced because of patent license fees, so their fad was short lived (Herlihy 2004, p. 126). British police may have patrolled by tricycle in the late 1880s (McCord 1991), and the Boston Park Commission police patrolled by high wheel bicycles during the same time period (Smith 1972). The Newark, NJ Police Department established its first bicycle squad in 1888 (http://www.newarkfop.com/museum.html).

By September 1892, the police in Orange New Jersey were being trained to ride modern safety bicycles for patrol and tandem bicycles for quick response to outbreaks and disturbances (Policemen on Bicycles 1892). By this time, the bicycle had evolved essentially to its modern form, the pneumatic tired, modern diamond frame safety bicycle (Herlihy 2004, pp.250-51). This same year, nearby Stamford Connecticut appointed Arnold Kurth as its first bicycle policeman (http://www.stamfordhistory.org/ph_1100.htm).

The following year saw Holyoke, Massachusetts also favorably experiment with bicycle patrols (Among the Wheelmen, 1893). By 1894, after some debate, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, Cincinnati, and Chicago all had active bicycle police patrols (McGurn, 1999; Smith, 1972). Thus, 1894-95 appears to be the beginning of wide-spread police bicycle use in the U.S. and indeed throughout much of the world. In Wellington, New Zealand, the police bought bicycles in the mid-1890s. Bicycles also were used by police in Ottawa and Winnipeg Canada around this time (Petty, 2001).

New York City started its unit in December 1895 with two bicycle policemen patrolling the streets most often used by cyclists. Within three months, the Chief of Police proposed making the bike squad permanent and extending it to three more precincts noting that bicycles increased police efficiency and were effective in patrolling and controlling scorchers (speeders on bicycles) as well as runaway horses. Police Commissioner Teddy Roosevelt, himself a cyclist, approved this proposal and within its first year of service the 29 man bicycle squad was responsible for 1,366 arrests. Soon, the squad grew to one hundred wheelers, including noted racer, "Mile-A-Minute” Murphy, and had its own station house. In his autobiography, Roosevelt praised the squad: “any feat of daring which could be accomplished on the wheel they were certain to accomplish” (Jeffers, 1994, p. 209).

An important impetus for these patrols beyond community patrolling was the control of “scorchers” as bicycle speeders were then called. In July 1896, after experimenting with 25 citizen wheelmen to patrol the streets and apprehend scorchers, the City of Denver began its two man team of "scorcher herders." They arrested twenty scorchers during their first day. The Denver "wheelcops" refused to use the sling shot device then reportedly being used in Chicago to hurl small lead balls at bicycle wheels in order to break spokes and bring the bicycle to a sudden stop (Whiteside1991, pp. 13-14). Similarly, in Grand Forks Minnesota, a bicycle patrol was started in the summer of 1896 to control scorchers and sidewalk cyclists (Spreng 1995, p. 281). Naturally, it fell to the bicycle police to catch the early automobile speeders as well (Held for Speeding Autos, 1902). Indeed, two police managed to catch and pull over a car transporting then President Theodore Roosevelt at a speed of 25 miles per hour when the speed limit was 15 mph (Held Up President 1905). The large chain ring on Arnold Kurth’s bicycle from Stamford pictured above would likely have been used to catch scorchers.

Smaller cities also adopted the bicycle for police use before the turn of the century. Fargo, North Dakota reports that all of its police were issued “Crimson Rim” bicycles in 1898 to help combat traffic problems. This amounted to at least ten officers (http://www.cityoffargo.com/police/NewWebSite/AboutUs/historyfpd.htm).

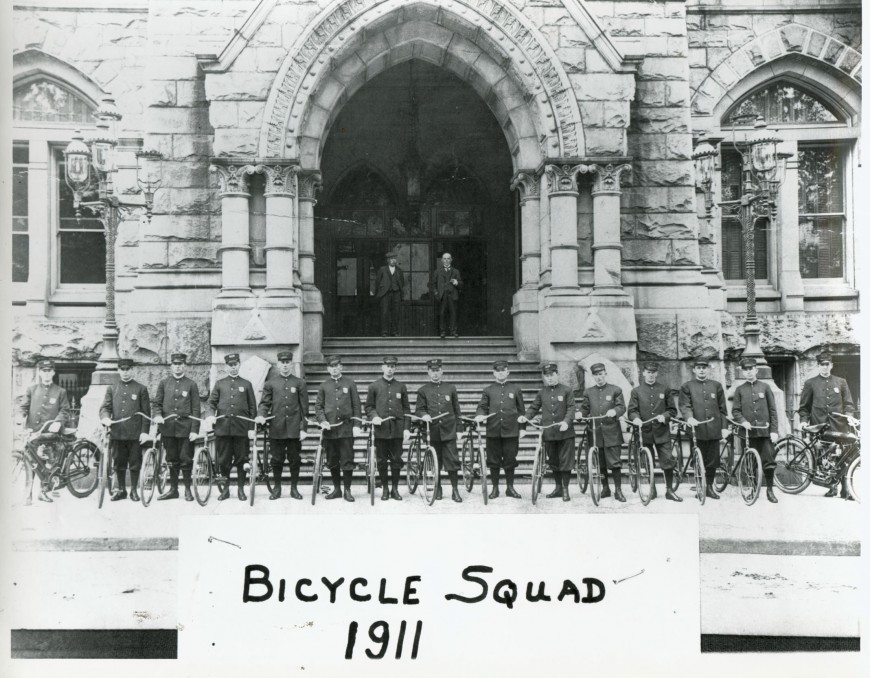

Bicycle use by police continued to increase in the early 20th century. In 1907, Indianapolis reported that its ten person bicycle squad made more arrests than any other police branch. Although, Indianapolis had two police cars by that time, it was predicted that the number of men on the police squad would increase (Gossip About Bicycles, 1907). The efforts of the bicycle squad continued to be exemplary in the following year. Of the 11,000 arrests made in 1908, the dozen members of the bicycle squad received credit for nearly 25% (Herlihy 2004, p. 318, citing Bicycling World 16 Jan. 1909).

By 1917, a bicycle trade publication estimated there were 50,000 bicycle police in the United States. It also reported that the five boroughs of Greater New York employed 1200 bicycle mounted patrolmen. These patrolmen could cover eight to nine times the territory of walking patrolmen (50,000 Bicycle Police, 1917-18). This is a tenfold increase over the original NYC bicycle squad of two decades earlier. Other communities also had police patrols at this time.

The estimate of 50,000 bicycle police was based on the assumption that one out of ten policemen used a bicycle and the article estimated a total of 500,000 police in the country. However, U.S. Census figures for 1920 indicate there were about 82,000 police and another 32,000 sheriffs. This would amount to somewhere between 8-11,000 bicycle mounted police or one bicycle officer for every 9-13,000 people. This could represent the high point of police bicycle use in the United States because the post World War I era saw a significant increase in police motor vehicle use.

Want to learn more? Download the full paper.

Comments

am impressed by the truths in this article. Cycling is indeed very important on so many levels and the world needs to embrace bicycles. I however insist that the challenges facing cycling should be addressed. I pride myself with having had an opportunity as an intern in a foundation, where we mostly delivered bicycles to community health volunteers. We also sold the idea of bicycles to entrepreneurs and high school students. M

01:35am, 11/27/2018Cycle

Great read. Wish it had more information regarding when technology came to police bikes. I.e. Walkie Talkie, 2 way radio..

10:18am, 08/17/2019